Reverse Estoppel: Application of the Rule in the Chinese legal system

This article will discuss the application of the concept of “reverse estoppel” as enshrined in related legal provisions, and the factors considered. This is based on a recent judgment from China's Supreme People’s Court’s (SPC) between VMI Holland B.V. (VMI) and Safe-Run Intelligent Equipment Co., Ltd. (Safe-Run) (See Supreme People’s Court’s (SPC) Administrative Judgment No. 663 ("Judgment No. 663") of 2021). A relatively new concept of “reverse estoppel”, which seems to be a reversed application of the principle of “estoppel”, is discussed in that case.

In patent invalidation proceedings and the related administrative litigations, the patentee may have to amend the existing claims in order to maintain the validity of its patent rights, or make a restrictive construction of the features in the claims to overcome the prior art documents submitted by the petitioner. On the other hand, in parallel patent infringement dispute proceedings, the patentee might be inclined to interpret the patent claims of its patent to the maximum extent possible, to effectively cover the accused infringing products. In order to maintain consistency in the scope of the same claims in patent administrative and infringement proceedings, the principle of estoppel has been introduced.

VMI vs. Safe-Run

VMI Holland B.V.’s patent (ZL 200880006690.4, entitled “Cutting Device”) has been challenged by Safe-Run in multiple invalidations and related administrative disputes due to a civil litigation over patent infringements, and one of the administrative disputes went all the way up to the Supreme People's Court through appellate proceedings.

In 2021, a final judgment (Judgment No. 663) was issued by the Intellectual Tribunal of the Supreme People’s Court reaffirming the validity of the VMI patent. Judgment No. 663 found that VMI’s target patent is valid and that “VMI did not interpret the technical feature differently or in opposite ways in the related proceedings of a civil litigation for patent infringement and the administrative litigation for patent invalidation, there is no ‘make profits at both ends’”. The final judgment reversed the first instance judgment and dismissed Safe-Runs’ appellate claim.

Specifics of the judgment

Noticeably, Judgement No. 663, addressed a concept of “reverse estoppel” proposed by Safe-Run asserting that VMI’s statements in the civil infringement case did not limit the specific number of “lifting beams”. Safe-Run alleged that this statement contradicts VMI's assertion in the administrative case concerning the validation of the target patent that there is only one “lifting beam”, and therefore, VMI was estopped from claiming in the administrative case that the claim feature “lifting beam[s]” [is not limited to one. Thus, a “reverse estoppel” was raised to stop patentee from making any statement in invalidation proceedings which contradicts what it said in the infringement proceedings.

VMI clarified that claim 1 of the target patent did not limit the number of lifting beams, and argued that a person skilled in the art could have known from the wordings of the claims, the specification and the accompanying drawings of the target patent, that the number of lifting beams should be set as few as possible and the structure of the lifting beams should be sufficiently compact. It never claimed that the specific number of lifting beams should be limited to one.

Reverse estoppel concept

Among the relevant patent law and regulations in China, the provision related to “estoppel” is Article 6 of the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Disputes on Infringement of Patent Rights” (“Judicial Interpretation”). The provision stipulates:

“The People’s Court shall not support any technical solution abandoned by the patent applicant or the patentee in the patent prosecution or invalidation proceedings through the amendment of the claims or specification or in the statement of opinion, which is claimed in the scope of protection of the patent right by the right holder in the case of patent infringement”.

From this provision, it can be seen that “estoppel” originally refers to “the abandonment in statement or modification of the claims in the patent prosecution or confirmation proceedings”, which constitutes a restriction or prohibition on reviving it in the related patent infringement proceedings.

In explaining what "reverse-estoppel" means, Judgment No. 663 cites the provisions of Article 3 of the “Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in Hearing Administrative Cases of Patent Right Confirmation(I)” (“Provisions (I)”), which reads:

“The people’s courts, when defining the terminology of the claims in administrative cases for the confirmation of patent rights, reference may be made to the relevant statements of the patentee that have been adopted by the effective decision of the civil case of patent infringement.”

It can be seen that the concept of reverse estoppel in Provision (I) is a restriction of “statements of claims in prior civil patent infringement cases” back on “corresponding claims in subsequent patent invalidation proceedings”. It differs from the estoppel rule in its order of application. Some scholars refer to this situation in which “a party may be estopped from reversing his statements made in a prior infringement proceeding in a later patent invalidation proceeding or patent invalidation litigation” as a “reverse estoppel”.[1]

1. Factors to be considered in the application of “reverse estoppel”

Factors to be considered in the application of “reverse estoppel”

In Provisions (I), some limitations to the principle, such as “reference MAY be made” and “EFFECTIVE adjudication” are emphasised.

First of all, according to Provisions (I), the limiting factors to be considered are:

- whether the prior civil judgment on patent infringement is effective;

- whether the relevant statements in the prior civil case on patent infringement have been adopted; and

- it is for reference purpose, the patent office or the court retain discretion in their case of patent validity.

Specifically, point (1) can be interpreted as: the applicable decision in a civil patent infringement case must be a valid decision, and a decision pending appeal that is not effective yet is not considered for the application of reverse estoppel. As to points (2) and (3), the rule can be interpreted as: even if the relevant statements of the patentee have been adopted in a civil judgement on a patent infringement case that has already entered into force, the binding nature of the statement in the judgement on the claims in the subsequent administrative case is not mandatory. It only serves as a reference for the later administrative proceedings.

Secondly, from the specific comments of Judgement No. 663 on the application of “reverse estoppel”, the factors can further be reviewed from three aspects: (1) whether the meaning of the relevant features in the claims of the case can be defined by the claims, specification and accompanying drawings of the patent; (2), whether the patentee had made different or opposite interpretations of the same technical feature in the civil litigation for patent infringement and in the administrative litigation for patent invalidation, in order to “profit from both ends”; and (3) whether the civil judgment of Suzhou Intermediate People's Court in Jiangsu Province[2] (hereinafter referred to as Civil Judgment of First Instance No. 780) cited by the appellant has come into effect.

The Judgement clarifies the principle that, when defining claim terms in a patent dispute, priority should still be given to the meaning in the claims, specification and accompanying drawings of the patent itself. The decision also added a factual consideration related to the particular case, namely, whether the patentee had adopted different interpretations in different proceedings in order to have the cake and eat it. On this point, the court took a pragmatic approach in its application of the principle of reverse estoppel. Specifically, this consideration reflects the court's assessment of the true intent of the patentee's statement/interpretation in the particular case in the actual circumstances when applying “reverse estoppel”, which not only avoids the patentee’s use of inconsistent statements to “profit at both ends”, but also protects the patentee from the dilemma of “loss at both ends” due to the inability to adopt an alternative claim construction in response to effective judgements.

In Civil Judgment of First Instance No. 780, to which Safe-Run’s reverse estoppel arguments relates, the court of first instance, namely Suzhou Intermediate People's Court (hereinafter referred to as Suzhou Intermediate Court), held that the number of lifting beams is not limited in the claims of the target patent and, through analysis, held that VMI’s statements in the patent invalidation proceedings that the lifting beams in the target patent were “separate” and the lifting beam structure was independent. Based on this holding, the Suzhou Intermediate Court held that the interpretation of the technical feature of “lifting beam” should be understood as a separate component to achieve the function of pushing up the rubber sheet, which did not limit the number of lifting beams. It thus held that there was no basis for Safe-Run to limit the scope of protection of the patent claims to a single lifting beam.

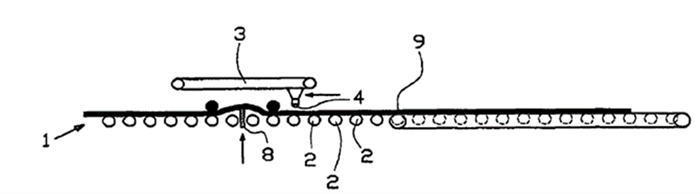

Finally, Judgment No. 663 analysed the “lifting beam 8” in the overall technical solution in the patent, referring to Paragraph 0007 of the specification and Figures 3A-3F of the specification (see the figure below, which is Figure 3B of the patent), and concluded that: “In the technical solution of the target patent, the technical effect to be achieved by the lifting beam 8 after lifting the rubber part 9 is that the rubber sheet lifted is put in a state of ‘rising in the middle and falling on both sides’”. Thus the court concluded that “although claim 1 of the target patent does not limit the number of lifting beams..., based on the limitation of the lifting beam structure, a person skilled in the art can understand that in the case of multiple lifting beams, the lifting beams should be sufficiently compact in order to achieve the above technical effect”. That is, the claim was clearly understood and supported.

Further, taking into the consideration of the above determination of the court of first instance on the “lifting beam” in the infringement case, the judgment concluded that VMI did not make different or opposite interpretations of the same technical feature in the civil litigation for patent infringement and later in the administrative litigation for patent invalidation in order to “profit from both ends”.

2. The role of “reverse estoppel”

The role of “reverse estoppel”

With the publication and implementation of the “Provisions (I)”, the rules of claim interpretation[3] are clarified.

An important purpose of “reverse estoppel” is to maintain the consistency of the parties’ interpretation of the claims in the bifurcated infringement and validity proceedings, thereby protect the legal rights of both parties in different proceedings and safeguard public interest. In this way, the patentee is prevented from “profiting at both ends” via inconsistent interpretation. The patentee is also assured that the scope of the maintained patent claims is not unduly restricted due to the improper application of “reverse estoppel”.

Summary

In summary, Judgment No. 663 shows that “reverse estoppel” in judicial practice is not only a legal tool to ensure consistent adjudications on the same issue by the administrative and judicial authorities, but also a legal requirement for the parties to observe the principle of good faith in parallel proceedings. The application of the principle of reverse estoppel effectively strengthens the protection of the legal rights of both parties and the interests of the public.

This article was co-authored by Aden Chen, Partner, Lawjay Partners and Bird & Bird Associate, Emily Zhao

[1] Jin Zheng, “On the Application of the Principle of Estoppel in Patent Justice (first part)", in Science, Technology, Innovation and Intellectual Property, 2011, No. 14.

[2] The Plaintiff, VMI Holland B.V. and the Defendants, Safe-Run Huachen Machinery (Suzhou) Co., Ltd., Safe-Run Machinery Engineering (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. and Shandong Shengshitailai Rubber Technology Co., Ltd

[3] Luo Xia, “Optimizing the Writing Mechanism of Patent Right Protection to Form a Protection Synergy”, in China Applied Law, 2021, No. 2.