IP in the UK’s Wind Energy Sector

The UK generates a substantial amount of renewable energy through wind power and it is set to increase generation in the near future by building more wind farms. As the UK seeks to become a world leader in the generation of renewable energy, we review the increasing patent activity in this technology and other aspects of building wind farms in the UK.

In October 2020 UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson delivered a speech at the Conservative Party annual conference. He announced that “the UK government has decided to become the world leader in low cost clean power generation – cheaper than coal, cheaper than gas; and we believe that in ten years time offshore wind will be powering every home in the country, with our target rising from 30 gigawatts to 40 gigawatts.”

The same day the UK issued an accompanying press-release proposing the following policies:

- £160 million will be made available to upgrade ports and infrastructure across communities like in Teesside and Humber in Northern England, Scotland and Wales to hugely increase our offshore wind capacity, which is already the largest in the world and currently meets 10 per cent of our electricity demand.

- This new investment will see around 2,000 construction jobs rapidly created and will enable the sector to support up to 60,000 jobs directly and indirectly by 2030 in ports, factories and the supply chains, manufacturing the next-generation of offshore wind turbines and delivering clean energy to the UK.

- Offshore wind will produce more than enough electricity to power every home in the country by 2030, based on current electricity usage, boosting the government’s previous 30GW target to 40GW.

- A new target for floating offshore wind to deliver 1GW of energy by 2030, which is over 15 times the current volumes worldwide. Building on the strengths of our North Sea, this brand new technology allows wind farms to be built further out to sea in deeper waters, boosting capacity even further where winds are strongest and ensuring the UK remains at the forefront of the next generation of clean energy.

- A target to support up to double the capacity of renewable energy in the next Contracts for Difference auction, which will open in late 2021 - providing enough clean, low cost energy to power up to 10 million homes.

These were quickly followed by a ‘Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution’ in November 2020 and a government White Paper entitled ‘Powering our Net Zero Future’ in December 2020 which repeated the UK government’s commitment to investing in wind power, alongside other renewable power sources and green technologies.

Wind power is already widespread in the UK and the government’s apparent commitment to expand it yet further makes the UK an important market for the deployment of wind technology. So, where does this technology come from? We review some characteristics of the patent landscape applicable to wind, including filing, grant and dispute profiles over time, to provide an indication as to how investment in wind technology has changed over time, who has made that investment and how they might expect to see a return on it.

We then review other kinds of IP important in the wind sector for deriving most value from operating wind farms in the digital age.

The patent searching carried out for this article was performed using Clarivate Analytics, who also provided the graphs included below.

Patents on wind technology

Patent filings over time

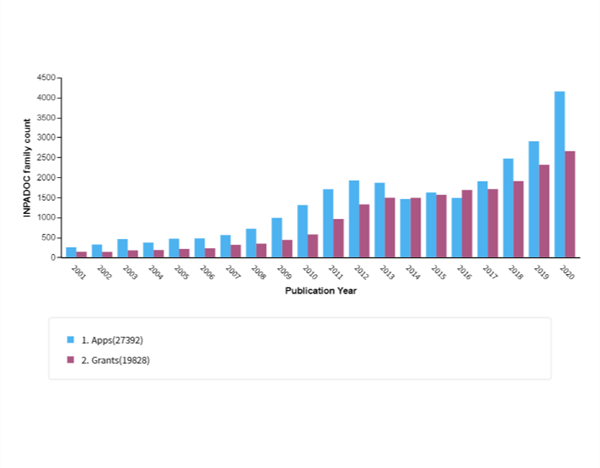

As technologies evolve, innovators file patents to protect their investment in research and development. According to our research, the international rate of patent filings in wind technology increased markedly between about 2007 and 2011, fell slightly before increasing again in about 2017 (see Figure 1, below showing number of patent applications filed by year of publication which is 18 months later than filing). This indicates that investment in wind technology increased substantially in the early years of the 21st century, leading shortly thereafter to an increase in the rate of patent filing. The downward trend in patent filing after about 2011 and 2017 could reflect a decrease in investment e.g owing to the 2008 financial crisis and the withdrawal of subsidies in the 2010s. The increase seen from about 2017 could relate to new avenues of technology opening up for innovation, e.g. in off-shore windfarms which began to appear in around 2009 but took a number of years to become recognised as an established proven technology which could be project financed as well as the occurrence of specific triggers such as increased Japanese interest following the Fukushima disaster in 2011.

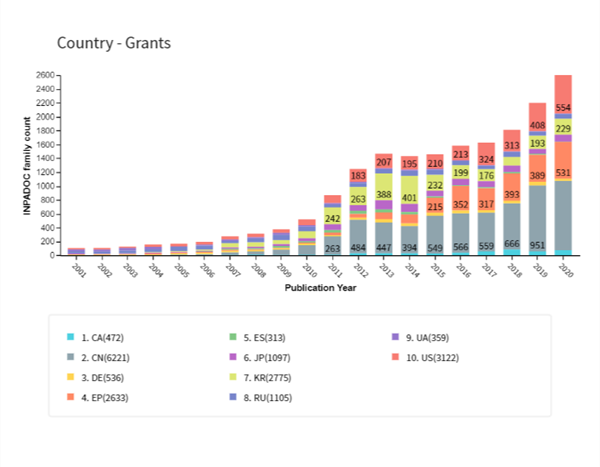

Filing a patent does not guarantee obtaining a patent: most countries and all major economies review whether the patent should be granted. However, the number of patents granting has followed a similar trend to those filed, some time behind. It can take years for patents to grant and the timeline is not fixed; therefore comparison of the numbers granted to the numbers filed is not altogether straightforward. What appears to be clear from this, however, is that the number of granted patents increased substantially between about 2007-2008 and 2013, plateaued until about 2017 and has since been increasing again.

Figure 1 – international filing and grant activity

Who is filing and being granted patents?

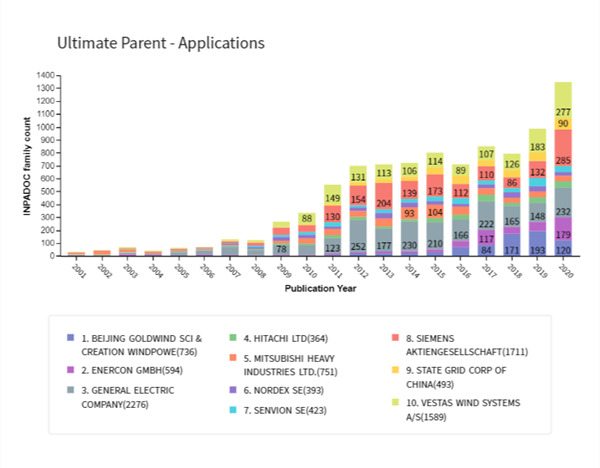

Taking the top ten companies filing patents in wind technology allows for some analysis. Between them, these top ten companies have filed almost exactly a third (34%) of the total filings worldwide in this period. The overall rate of filing of these ten companies combined follows a similar trend to the total international filing behaviour discussed above, with substantial increases between about 2007-2008 to 2011 and again more recently from about 2017, although the period from about 2011 to 2017 shows slightly different behaviour to the overall international behaviour discussed above. See Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 – top ten companies by total number of patent applications 2001-2020

Early leaders General Electric Company, Siemens and Vestas drove much of this filing behaviour. More recently, since about 2016, Beijing Goldwind has become one of the higher-filing companies. Enercon moved into the top 4 in 2020.

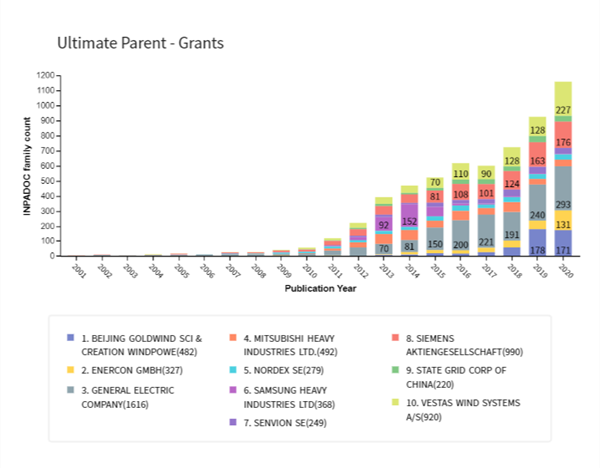

Examining the rate of patents granted to the same companies may provide some indication who is ‘getting in first’ with comparable technology. However, many other explanations could be available, such companies filing in different countries which may apply more or less rigour to their patent granting process. In any event, the data (see Figure 3, below) shows that, of the companies filing the largest number, General Electric is particularly successful, with approximately over 70% as many patents granted over this period as it applied for. Vestas and Siemens, by comparison, each have just under 60% as many patents granted over this period than applied for, with both Beijing Goldwind and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries lying between these points at around 65%. Those numbers cover the total time period, however, and some attempt to analyse the trends within the time period may be of more interest.

Figure 3 – top ten companies by total number of patents granted 2001-2020

Thus, for example, the figures for General Electric indicate that a proportion of its patent filings are taking longer to grant recently than previously: in 2020 it received grant of more applications than it had filed in any one year, and in 2019 it received grant of more applications than it had filed in any years except 2012. In contrast in 2013 and 2014, for example, similar numbers were granted to what had been filed some years before (2009 and 2010). This may merely indicate increasing patent office delays, a change in filing behaviour as regards where the patents are filed, or the like. However, it would also be consistent with the patents requiring more time and resource to achieve grant, potentially indicating that the field is becoming saturated. Vestas likewise had more patents granted in 2020 than they had filed in any previous year. Siemens’ data is more complex, since their rate of filing has varied more than the two previously mentioned companies. Siemens’ approach also appears to have borne fruit, with large numbers of grants in 2019 and 2020 compared to previous years. Beijing Goldwind shows a somewhat different trend, with a high rate of patent grant closely matching its rate of patent filings only a short time before. This is consistent with the patents being examined less rigorously (e.g. in a different patent office than those of the other companies discussed) or of a more innovative technology that is leading to more rapid patent grant.

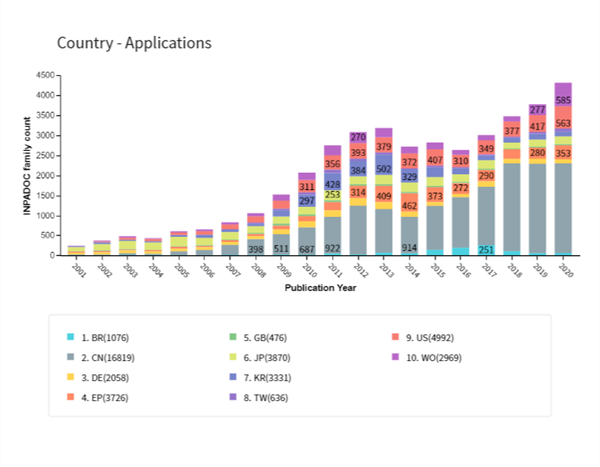

Some indications as to how to interpret the data about individual companies may be drawn from examination of where the patents are being filed and granted – see Figures 4 and 5 below.

Figure 4 – top ten countries or regions (EPO) for patent filings 2001-2020

Figure 5 – top ten countries (EPO) or regions for patent grants 2001-2020

Taking the major patent offices in the US, Europe, China, Japan and Korea, the US – 63% – European Patent Office – 70% – and Korea – 83% are granting patents at a much higher rate than the more moderate China – 37% – and Japan – 28%. This could be a factor in the above analysis of the success rate of different companies, on the premise that each company will as a minimum file in its own home territory, influencing the grant rates of General Electric, Siemens and Vestas positively compared to Beijing Goldwind and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

Leaving the applicant aside, the country data gives an indication of the international expectations of the industry – substantial filings in Brazil and Taiwan, for example, joining the often-covered countries/regions are likely driven by an expectation of wind energy deployment in those countries. The relatively high level of national filing in the UK (GB filings), which are separate to the coverage of the UK through the European Patent Office, may be indicative of the interest in the UK as a market for deploying wind power technology. Equally, the UK-only filings may be indicative of domestic innovation by smaller companies who may be motivated to file their patents on a more modest scale, perhaps protecting only their home market to save on the investment costs of securing patent protection. Large international companies (particularly those headquartered outside the UK) would be likely to seek protection in the UK via an application through the European Patent Office. Our qualitative review of the applicants for these GB-only filings suggests that it is a mixture of the two: many UK companies and individuals are represented, but large international companies are also filing GB patents. The former shows that there is a substantial body of home-grown innovation in the UK wind power industry. The latter supports the proposition that the large international wind technology business view the UK as a key market in which to protect their technology, since they appear to be investing in country-specific filing in the UK as well as through the European patent office where their filings are substantial.

The country data also shows where patent coverage is thickest, with large numbers of patents held by relatively small numbers of large international companies. This landscape presents potential difficulties for others trying to manufacture or supply into these countries, including the UK. A smaller manufacturer in need of a licence to third party patents may find it difficult to obtain such a licence on good terms if they do not have their own patents backing up their position. The top ten companies between them hold about 30% of the granted patents worldwide, giving each of them significant bargaining power in such licensing arrangements – General Electric alone holds over 8% of granted patents. In that respect, from the above it will be clear that there is no UK-based company in the top filing companies. A qualitative review of UK-based companies filing in this technology does reveal a range of different UK-based companies filing applications for wind technology, including the likes of Rolls Royce, several UK universities and a range of smaller companies and individuals.

Patent disputes

Such a situation has the potential to lead to disputes, with large, well-funded companies holding multiple patents asserting them to keep others out of the market, or smaller companies with a few valuable patents on occasion taking on a larger competitor in order to carve out their position in the market.

The availability of information about litigation varies considerably between different countries in Europe. In the UK, patent disputes in the Courts of England and Wales are publicly reported and may be searched, but any disputes in Scotland are not. In many other European countries full details of court proceedings are not readily accessible. Nevertheless, our research has uncovered some patent disputes in many of the larger European markets: France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and the UK. As might be expected from the various characteristics of the patent litigation systems in Europe, the incidence of cases in Germany is much higher than in the other countries (at least, so far as those cases could be discovered by us) with over 30 cases compared to no more than 3 cases in any other country. With such low numbers of cases, attempting to draw any trend would be misguided. However, one notable feature is that a substantial number of cases have featured Wobben, whom we understand is related to Enercon, or in some cases Enercon itself. Vestas, Siemens and General Electric have also featured in cases which we have discovered; however, the larger international patent holdings of these companies do not appear to have translated into their bringing any significant numbers of patent enforcement actions so far as we can tell.

Other IP for deriving value from wind farms

The increasing sophistication and digitisation of wind farms and the management of their performance depends in part on two things: data and AI. Data fed back to central control is a key digital asset for modern energy companies controlling wind farms. Likewise, AI built into control systems to augment or replace human control is on the rise.

An AI control system could be subject to patent protection in the right circumstances (as discussed below) but often this is not the case. And data generated from operation of a farm, or needed to train AI systems on another farm, certainly cannot be patented. Below we consider what other IP rights are available for protecting these valuable things.

Protecting and exploiting data

Data may come in many shapes and sizes. If the data is about customers or employees, issues of data protection (in particular under the GDPR) will arise, but that is not the subject of this article. Data in general is gathered into a central repository in such a way that the whole collection of data becomes much more valuable than each piece was: the performance data collected across an entire sub-grid rather than just on a single turbine, for example, may allow richer analysis.

In part this fact is reflected in the legal tools available to protect commercially valuable data. There are four main legal tools that may come into play, each with its own role:

- Confidential information/trade secrets;

- Contractual restrictions;

- Copyright; and

- Database right.

Protecting data as confidential in the UK requires that the data have a 'quality of confidence' and, generally, steps be taken to ensure the data is not publicly accessible. In practice where data is e.g. performance data about a distribution system it is likely that the data will not in fact be readily accessible to outsiders but suitable measures should be put in place to ensure this is the case in order to show the information is regarded as confidential. Restrictions will need to be put in place on employees' use of the data and on any third party with whom it may be desirable to share the data. The requirement for "reasonable steps" to be taken to protect confidential information in order to satisfy the recently introduced definition of a trade secret under the EU Trade Secrets Directive (which was implemented in the UK prior to Brexit) also warrants this approach.

These restrictions overlap with the next tool, contracts, which should be used to embody these restrictions. The contract should make clear that the data set is confidential and what may or may not be done with it and by whom. If the data should be returned from a third party after their permitted use of it ceases, some thought must be given to how this can be practicably achieved.

Contracts can also be used to license the rights that may arise under copyright or database rights if it is desirable to share the data with a third party. However, the application of these rights here is not straightforward.

Copyright protects defined categories of 'works': literary works, musical works, broadcasts, etc. It protects the copying of or dissemination to the public of these works. Within this framework, it is possible that a collection of data may in some circumstances qualify as a literary work in the form of a table, compilation or database. A database is the most likely to be relevant here but in order to qualify for copyright protection the database in question must be the intellectual creation of an author (or group of authors) by reason of their selection and arrangement of the materials in the database: it is questionable whether this criterion can be fulfilled with a collection of, for example, technical performance data where the selection and arrangement may be minimal. However, if there has been intellectual investment in deciding what types of data should go into the database and how they are to be arranged, it is possible that protection may be available. Note, however, that this copyright does not protect the individual items of material in the database which may be another key limitation in this context.

Besides the possibility of copyright, some databases may also be protected by database right. Confusingly, this 'database right' is a different legal right than the database flavour of copyright. Note also that this was an EU-derived right and may be subject to change, although for present the right has been retained in UK law after Brexit. A database for this purpose is a collection of individual data items arranged in a systematic or methodical way and individually accessible. In order to qualify for protection by a database right, the database must additionally have been the result of substantial investment in obtaining, verifying or presenting its content. Importantly, this investment must be in those specific activities rather than in creating the individual data items. And, like the copyright that exists in some databases, the database right does not protect the individual data items. Instead, the database right provides its owner with the ability to prevent the extraction and/or re-utilisation of a substantial part of its content.

Protecting AI

At one level, AI systems are just like any other computer software. Thus the same IP rights may be used for their protection: the source code for the AI is protected by copyright. The source code can also be kept confidential such that it becomes a trade secret.

If it is new and inventive, an AI-based system may be capable of protection by filing a patent. However, in Europe, computer programmes "as such" are not patentable: the patent applicant must demonstrate the invention has some real-world 'technical effect', e.g. as a control system. In general, there is no reason why this cannot be done for a system involving AI and control systems involving AI control provide a clear hypothetical example of this. However, AI systems concerned principally with analysis present a much more challenging area for potential patent filings. Not only are computer programmes "as such" excluded from patenting but so too are mental acts and mathematical methods. Thus one can envisage that patent applications in an area such as AI systems for demand/supply balance control systems might be capable of patent protection but the invention must be expressed in terms of what the system achieves and not how its analysis is performed. The latter will also need to be explained but will not be the subject of protection where not alloyed to the system's overall effects.

The two together

So far so good. But there is a significant interaction between data sets and AI. AI is often used to deal with problems with large data sets where humans struggle or take too long due to the amount of data. Machine learning AI systems of the kind used here must usually be trained by supplying to them appropriate example or simulated data sets for them to learn on before they are unleashed on the real world. This raises a number of points, such as:

- First, training data sets may be very valuable. The AI itself may be generic but comes into its own when trained for the particular application. Or the AI might be subject to a patent application which discloses its basic mode of operation but much of the value of the AI system may lie in using an appropriately trained AI system. This may give rise to opportunities such as the co-licensing of a patent and one or more accompanying training data sets in a model not dissimilar to that used in chemical and pharmaceutical industries where important 'know-how' accompanying a patent licence can be a very valuable part of such a transaction.

- Second, in many cases the holder of the data set will not be the developer of the AI system but someone who wants to use an AI system developed by another. For a productive collaboration, both parties should ensure they consider how they intend to protect their asset before sharing with the other.

- Third, the training data set will generally have been carefully selected. Often a considerable amount of effort will have been expended in optimising the content of it: this may assist in showing that it is protectable by database right in particular, copyright and (if kept secret) as confidential information/a trade secret having a necessary quality of confidence.

Some consideration must also be given to the reverse situation. An AI control system may gather a valuable data set. Of course this can be done in such a way that the data is kept confidential and contractual restrictions can be imposed on employees, sub-contractors, consultants, etc, in the usual way.

But, can the data set also qualify for protection by copyright or as a database right? If so, who owns that right in various scenarios, such as if the AI system is supplied by a third party? Interestingly, copyright law in the UK provides for the situation of 'computer-generated works' of which these might be an example. The person(s) who made the arrangements for the computer to generate the work is considered in law to be the author of the work, although this area has not been tested for AI systems. However, the same is not true of the database right which does not have this provision: it may well be argued that the same principle should apply since, at least in the right circumstances, the investment in the AI system could be said to be the investment in the obtaining, verifying and presenting of the data items in the database. However, this has not been established and clearly opposing arguments are readily available.

As regards confidentiality, if the AI system is set up such that the data is only accessible by certain people there seems to be no reason why the involvement of the AI system should undermine the necessary quality of confidence needed to acquire protection for that information. However, one can imagine a situation in which this position could be undermined in circumstances where a less sophisticated AI system that gathers very mundane data also gathers data of greater potential value but does not itself discriminate between the two.

Conclusions

Several companies have global patent filings in the wind sector far in excess of any others. We have not analysed the fine detail of what technologies these relate to or how those may be shared between the different players but this may prove a driver of the types of wind technology that may be deployed, since wind farm builders and operators will need to consider their licensing position before purchasing or operating such technology.

Once a farm is operational, in the right circumstances data assets can be protected by powerful legal tools. However, consideration should be given to which legal tools are best for the particular situation and the systems then implemented in a way that will best ensure protection is acquired.

Our lawyers at Bird & Bird can advise on patent risk and licensing, or on putting into practice a system to help businesses protect their digital assets.