When Illegality Challenges Defences: How Hong Kong Courts Balance the Competing Claims of Victims and Downstream Recipients

The doctrine of illegality in Hong Kong – Part 3

Introduction

In Part 1 (read here) and Part 2 (read here) of our three-part series on the doctrine of illegality, we provided an overview of the fundamental principles governing how illegality affects civil claims, and examined how foreign illegality affects restitutionary claims. This comprehensive examination has laid the groundwork for understanding the complex interplay between illegality and civil remedies under Hong Kong law.

In this final part, we examine a critical question: how illegality affects the two principal defences to unjust enrichment claims — namely, change of position (the “COP Defence”) and bona fide purchaser for value without notice (the “BFP Defence”). This issue frequently arises in asset recovery in fraud cases and represents one of the most contested areas in the application of the doctrine of illegality.

Can a defendant rely on these defences if his relevant conduct is illegal?

Refresher on the defences to unjust enrichment claims

The COP Defence requires the defendant to demonstrate, inter alia, that he changed his position in good faith such that it would be inequitable in all the circumstances to require him to make restitution. The BFP Defence is available where a defendant purchased legal title to the subject property for valuable consideration in good faith without notice of the prior equity at the time of transfer. Both defences incorporate a good faith requirement, which becomes crucial when illegality is alleged.

A typical fact pattern involves victims of online romance scams or business email compromise fraud pursuing restitutionary claims against downstream recipients of the defrauded funds. Such downstream recipients, when defending unjust enrichment claims, commonly assert that they had no knowledge of the underlying fraud and received the funds pursuant to what they believed were legitimate commercial transactions, such as payment for services or goods provided, or through currency exchange services. The question then arises: does the illegality of their conduct (whether under domestic or foreign law) preclude reliance on these defences?

Two competing approaches

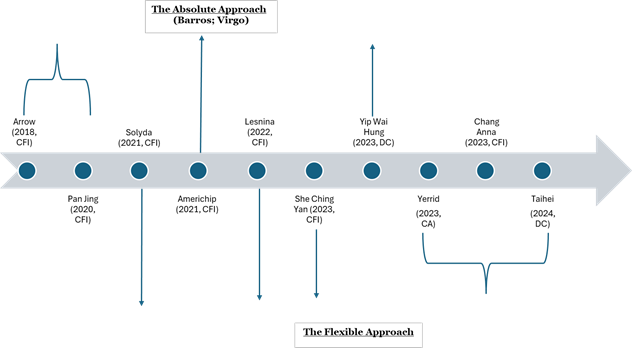

This remains a rapidly evolving area of law. The case law suggests that there are, broadly speaking, two distinct approaches.

(1) The Absolute Approach

In Arrow Ecs Norway As v M Yang Trading Ltd[1], the plaintiff sued downstream recipients of defrauded funds in unjust enrichment. The court found that the defendants’ operation of the money service business contravened the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing (Financial Institutions) Ordinance (Cap. 615) (“AMLO”), and that the receipts and payments out therein (constituting the ‘change’ under the COP Defence) were carried out illegally. On this basis, the court rejected their COP Defence on the basis of domestic illegality and granted summary judgment in favour of the plaintiff. As to the effect of illegality on the COP Defence, the court explained that:

- The court was bound to accept (at the time) Tinsley v Milligan[2] and Barros Mattos Junior v General Securities & Finance Ltd[3]. The COP Defence cannot be relied upon where the change is regarded by the court as “wrongful”, and where “the recipients’ actions of changing position were treated as illegal… the court could not take them into account and had no discretion to do so, unless the illegality was so minor as to be ignored on the de minimis principle”.

- Further, “the recipient cannot put up a tainted claim to retention against the victim’s untainted claim for restitution”.

- Separately, based on the same facts supporting the illegality argument, the defendants did not act in good faith, i.e. “it would be inequitable, unconscionable, and thus unjust” to deny restitution.

This approach in Barros and Arrow was adopted in DBS Bank (Hong Kong) Ltd v Pan Jing[4], a case involving foreign illegality. The defendant was a downstream recipient of defrauded funds who sought to rely on both the COP Defence and the BFP Defence to defeat the plaintiff’s unjust enrichment claim. The defendant claimed that he received the funds through a currency exchange arrangement via a friend, which was found to contravene PRC laws. In granting the summary judgment:

- The court rejected the COP Defence, following Barros and Arrow.

- The court rejected the BFP Defence, citing Virgo[5]: “the defendant cannot be considered to have provided value for the property if it was transferred pursuant to an illegal transaction”. Notably, while the plaintiff also argued that the defendant did not provide value because the alleged currency exchange contract was void under PRC laws, the court considered that this issue should not be dealt with summarily and refused to reach a conclusive view.

- As to the defendant’s contention that he was acting in good faith regardless of whether the exchange transaction was illegal because he relied on his friend to deal with matters legally, the court held that no triable issue was raised to show that he (as an experienced businessman) did not know that the exchange would be conducted illegally.

- The court stressed that, for both defences, it was not necessary for the plaintiff to show that the defendant knew of the fraud, so long as the money was transferred pursuant to a transaction that was itself illegal and the evidence did not support the defendant’s lack of knowledge of how the exchange would be effected.

Similar reasoning can be seen in Americhip Inc. v Zhu Hongling[6] (a case of foreign illegality involving currency exchange conducted in breach of PRC laws) and Yip Wai Hung v Shanghai Business[7](a case of domestic illegality involving the conduct of money exchange business in breach of the AMLO). In Yip Wai Hung, it was held that once illegality was established, the COP Defence would be defeated as it “require[d] good faith as an element”.

Under the Absolute Approach, once a defendant is found to be a “wrongdoer”, or his “actions of changing position” are illegal (save for de minimis cases), or value was transferred pursuant to an “illegal transaction”, the COP Defence and BFP Defence would likely, if not automatically, be defeated with little or no evaluative exercise.

(2) The Flexible Approach

Solyda SRL v Wu Ge[8], like Pan Jing, involved foreign illegality where the defendant was a downstream recipient of defrauded funds seeking to rely on the COP Defence and BFP Defence. However, the court reached a markedly different conclusion, rejecting the plaintiff’s summary judgment application and signalling a more nuanced approach to illegality in this context:

- Pan Jing was distinguished on the facts, in that (i) the defendant in Solyda was a housewife who claimed to be introduced by an insurance company director to currency exchange services which she allegedly believed were legitimate but in fact contravened PRC laws, whereas (ii) in Pan Jing there was no reason to support the defendant’s contention that he as an experienced businessman did not know the exchange would be conducted illegally. It was held that there was a triable issue, insofar as good faith was concerned.

- The court noted that the issue of the extent to which illegal conduct precludes a defendant from relying on the defence is a “developing point of law”, and that “Barros has also been criticised for being overly rigid due to its absolute approach that all kinds of illegality (save de minimis ones) would deny the defence… the better view is that the defendant should only be disqualified from the defence by illegality where the criminality is significant and not trivial”. It was held that this issue could not be determined summarily.

Significantly, Solyda (which adopted the Flexible Approach) was not referred to in the subsequent decision of Americhip (which adopted the Absolute Approach, see above).

The tension between these approaches was further highlighted in Lesnina H DOO v Wave Shipping[9] (a case involving foreign illegality). The court considered Barros, Pan Jing and Solyda, concluding thatthe issue of whether illegality precludes reliance on the two defences involved conflicting legal authorities, making it inappropriate for summary determination. The court indicated that a preferable approach would be “one that measures the gravity of the defendant’s criminal conduct against the impact of allowing the defence”. The plaintiff’s summary judgment application was rejected on the basis of triable legal and factual issues[10].

A significant development then occurred in She Ching Yan v Cai Yunxiang and Ors[11], a case of foreign illegality where the defendant was a downstream recipient of defrauded funds through a currency exchange arrangement contravening PRC laws. Relying on Ryder[12], the court drew a clear line between the treatment of domestic and foreign illegality cases. Accordingly:

- Arrow (a case of domestic illegality) had no application.

- The court refused to follow the Absolute Approach in Barros, Pan Jing and Americhip. Instead, the court should “consider in each case what should be the proper effect or consequence of a foreign illegality” taking into account the type and seriousness of the illegality together with other relevant circumstances.

- However, where the performance of a contract or transaction within the ‘Type 2’ case in Ryder was involved, the court should refuse to recognise or give effect to the transaction. In that event, the court should apply a strict approach, and the COP Defence and the BFP Defence would fail.

On the facts, the court determined that this was a ‘Type 2’ case. The court refused to recognise the currency exchange transactions altogether, without proceeding to evaluate the seriousness of the contravention against PRC laws. Summary judgment was entered in favour of the plaintiff. Out of an abundance of caution, the court observed that, even if the correct legal approach for all four types of cases under Ryder would require an evaluative exercise based on the seriousness of the foreign illegality, the defendant would still fail to raise any triable issue on the facts.

While the principles established in She Ching Yan were subsequently adopted in Chang Anna I No v Caibaolong Trading[13] and Taihei Dengyo Kaisha Ltd v Zhao Yizhe[14], this decision (as well as Solyda and Lesnina) was notably absent from the reasoning in Yip Wai Hung, which reverted to the Absolute Approach (see above). This should be assessed against the context that, in Yip Wai Hung, the court found that there was no change of position in the first place, and the defendant accepted that illegality defeated the COP Defence – potentially limiting the precedential value of this aspect of the decision.

Finally, in The Yerrid Law Firm v Qiansbaizi Trading Limited and Another[15], the Court of Appeal questioned the Absolute Approach in the context of domestic illegality (violation of the AMLO). The court referenced Solyda and Lesnina (cases of foreign illegality), noting that it is not normally appropriate in a summary procedure to decide controversial questions of law in developing areas. Crucially, the Court of Appeal held that the impact of illegality on defences to unjust enrichment claims should be assessed by the principles in Monat[16] rather than Tinsley, suggesting a move away from the rigid Absolute Approach.

Conclusion

The law regarding how illegality affects defences to unjust enrichment claims is in a state of rapid evolution. Recent authorities suggest a judicial shift away from the Absolute Approach, under which illegality (save for de minimis ones) would preclude a defendant’s reliance on the COP Defence and BFP Defence with no or limited evaluation of the conduct and other circumstances, towards the Flexible Approach which requires a case-by-case evaluative exercise considering the seriousness of the illegality, the defendant’s culpability, and the proportionality of denying the defences. This evolution appears to mirror the broader trend in Hong Kong law towards a more nuanced and contextual approach to illegality questions.

Despite these developments, significant uncertainties remain. It was queried in Wong Chi Hung v Lo Wing Pun & Ors[17] whether She Ching Yan concerns a ‘Type 2’ case. It remains to be seen whether the approach in She Ching Yan, under which courts should refuse to recognise or give effect to transactions falling within ‘Type 2’ cases under Ryder, will be endorsed in future decisions. Clarification from higher courts would be welcome to provide certainty in this important area of law; although in practice a plaintiff may be better off expediting the case for an early trial than trying its luck in appeal.

From a practical perspective, these developments have significant implications for litigation strategy. Until the law is settled, summary judgment applications against downstream recipients in fraud cases who rely on the BFP Defence and COP Defence are likely to face greater scrutiny. Courts may be increasingly inclined to find triable issues requiring full trial, particularly where the seriousness of the illegality, the defendant’s knowledge and the proportionality of denying the defences are in dispute. Legal practitioners should closely monitor future developments and consider the evolving judicial preference for the Flexible Approach when advising clients on both bringing and defending such claims.

The principles and case law examined in this three-part series provide a foundation for understanding these complex issues. Practitioners must remain alert to ongoing judicial developments in this dynamic area of law.

This article was written with the assistance of James Yeung.

[1] [2018] HKCFI 975.

[2] [1994] 1 AC 340, which was discussed in Part 1 of this series.

[3] [2005] 1 WLR 247.

[4] [2020] HKCFI 268.

[5] Virgo, The Principles of the Law of Restitution, 3rd ed, 2015.

[6] [2021] HKCFI 3530.

[7] [2023] HKDC 401.

[8] [2021] HKCFI 1825.

[9] [2022] HKCFI 1070.

[10] One defendant contended that it only received the ‘tainted’ funds for goods sold and delivered; there was no evidence that it had participated in underground banking itself.

[11] [2023] HKCFI 592.

[12] (2015) 18 HKCFAR 544, which was discussed in Part 1 of this series.

[13] [2023] HKCFI 2782.

[14] [2024] HKDC 222.

[15] Yerrid Law Firm v Qiansbaizi Trading Ltd.

[16] [2023] HKCA 479, which was discussed in Part 1 of this series.

[17] [2025] HKCA 370, which was discussed in Part 2 of this series.